The sun has barely risen, yet at the hour of 7am I am keenly assaulting breakfast, the staff having been awake and dressed for hours in its preparation. The timing was at their suggestion. Several are obviously not fully alert, rubbing eyes that remain glassy. Sheepish in response to their obvious fatigue I fix my eyes firmly upon my food. Except for the one at which I sit, all the other tables are empty. I eat toast and butter, omelette, and cereal with curd and sugar. This is followed with diced pineapple, rockmelon and watermelon. Outside, except for isolated clumps of vegetation, the landscape is barren desert. It’s spectacular.

The car navigates the sealed road to Jaisalmer, this time on the left hand side of the road, the right side. But at this hour no other conveyances are awake. The road is all mine, ours. I look vainly in the hope of spying a Great Indian Bustard, Ardeotis nigriceps, a member of the family Otididae. It was proposed as India’s national bird but in the final count lost out in favour of the Indian Peafowl, Pavo cristatus; one of the reasons flying against the bustard’s choice was its potential susceptibility to an unfortunate range of obvious, though crude, appellations. Personally, I thought the peacock just as easy a target for cheap expressions of crudity. The Great Indian Bustard, as its name alludes, is a large brown, black and white bird, standing over a metre high when fully grown. It’s got a long neck and long legs; hard to miss if the bird is standing up. The species is now critically endangered, and though previously widespread in India and Pakistan, its range is steadily being reduced to isolated pockets. The preferred habitat is arid and semi-arid grassland, and the Thar Desert, and its Desert National Park of over 3,000 km2, is a major refuge for the species. Its diet is mainly one of grasshoppers and related insects, plus some berries, seeds, groundnuts, rodents and lizards when these are in season. Unfortunately diet works two ways, the Moghul Emperor Babur taking a particular fancy to the bustard’s cooked flesh. The British India Army officer, ornithologist, Indologist, politician and one time director of the East India Company, Colonel William Henry Sykes (1790-1872), also considered it a delicacy and a top game-bird, noting the Great Indian Bustard was common in the Deccan, where ‘gentlemen’ had been able to shoot thousands of the birds. I never saw a single one, not even one dead on the side of the road.

***

Some kilometres out from my hotel I pass a massive red brown building that I mistake for a fortress. It’s another hotel. But the Jaisalmer fortress is the more imposing of the two. It is one of the largest fortresses in the world, being initially built in 1156 by the Bhati Rajput ruler Rao Jaisal, from whom its name is derived. The sandstone walls glow honey-gold at sunset, thus the fort’s popular title, the ‘Golden Fort’. The fortress defences consist of three walls and 99 bastions, most of which were constructed between 1633 and1647. In the 13th Century the fortress was captured by Ala-ud-din Khilji, the Rajput women inside its walls committing Jauhar to avoid capture and defilement.

Jaisalmer was a major centre for trade to Persia, Arabia and Africa, however, this role declined with the advent of British rule and the development of the port of Bombay, now Mumbai. Since Partition in 1947, Jaisalmer has assumed significant strategic importance. As part of the pre-emptive 1971 air strikes known as Operation Chengiz Khan, against forward Indian air bases and radar stations, Pakistani aircraft attacked Jaisalmer. These succeeded in damaging underground power cables, resulting in the temporary loss of power supply and disruption to telephone communication. This and other air strikes in western India by the Pakistan Air Force heralded the opening of formal hostilities between the two countries in what had at first been simmering border clashes. Pakistan attempted to use the same tactics as those of the Israeli air force at the commencement of the Six Day War of 1968. Israel neutralised the superior numbers of Arab aircraft by a combination of surprise and consequent achievement of air superiority. But in the case of the Indo-Pakistani War of 1971, the strategy was foredoomed to failure, the Pakistanis possessing inadequate aircraft and munitions, the retaliatory air strikes by superior numbers of Indian aircraft gaining complete air superiority over Pakistan within two days.

However, the Jaisalmer fortress remains under threat. But these are threats due to seismic activity, water seepage, derelict houses, haphazard building construction that has interrupted the fortress’s drainage system, impacts associated with the growing numbers of tourists, commercial activity, vehicle movements, and the lack of a co-ordinated approach to the conservation and restoration of the fortress by authorities responsible for its upkeep. Unlike many other Indian forts that at Jaisalmer is built on weak sedimentary rock which makes the foundations vulnerable to water seepage. This has already led to the collapse of the ‘Queen’s Palace’, the Rani Ka Mahal, as well as sections of the outer and pitching walls. Some five to six hundred thousand tourists visit the fort each year; cumulatively over time, that’s a big environmental footprint.

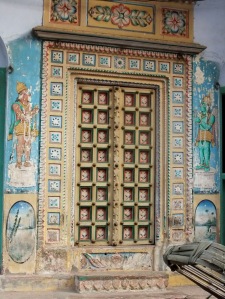

Intent on adding in my own little way to this impact I am deposited at the car park that adjoins the fort’s First Gate. I will spend the whole day wandering about at leisure. The driver warns about the risk of thieves, and merchants given habitually or from necessity to easy lies and fabricated stories. Mindful of this, my hand firmly in contact with my wallet, I enter this world of delights. But it is obvious it is a place without secrets, for I am not alone, and there are tourists everywhere. The city is firmly on the tourist map. There is even a wall sign inside the Second Gate that proudly displays that a particular business establishment is under Australian management; ‘8 July Restaurant, Vegemite, run by Australian Resident, Estb. 1983’. Well, there go the bargains. Not to be outdone another sign overhanging the inner wall of the First Gate proudly heralds the ‘Ristorante Italiano Jaisal Italy’, and further on there’s a German bakery! So there you have it. I wander all the way over to India, and find multiculturalism in action here as well. And just to underline Jaisalmer’s sense of the cosmopolitan, there’s a ‘Pepsi’ sign vying for space and attention between an advertisement offering foreign money exchange, and an internet cafe. Unfortunately, on this day, the little metal box claiming to be the headquarters of the Tourist Assistance Force was closed for business. Above all of this loom the salutary and rounded bastions of the fortress, these jutting out at strategic positions, the harsh and indifferent masonry of several softened only by delicate window turrets positioned high on their rim.

The opening courtyard behind the First Gate is faced with stone worn smooth by years of use, the side walls of the inner Second Gate polished almost to a shine by thousands of hands that over the years have been run across their surface. Through this speed tiny black and yellow autobicycles, their horns blaring a warning as they turn the final sharp corner prior to entering the Dusshera Chowk, there to quickly deposit their occupants before hurtling back in search of more clients. The sharply curved entrance through the vault of the Second Gate was a feature first intended to slow and befuddle attackers, now it is an extended dodgem rink where pedestrians anticipate the frenetic passage of taxis. The car park at the entrance to the fort provides a constant harvest, for tour cars and buses are endlessly disgorging day trippers, me not the least, each grasping a camera misbalanced by an oversized lens, each traveller bent ever lower by the packs carried on their backs, the contents heavier by the hour. Between the First and Second Gates are the shops of hopeful businessmen, their wares those of religious imagery, brass figures of assorted gods, bottled water by the pallet load, and brightly embroidered shoulder bags and patchwork wall-hangings blended from the salvaged remnants of tribal costumes.

In the Dusshera Chowk abound sellers of postcards, books and sundry items of clothing. I am for some minutes entertained by the assorted stock on display at the ‘Pappu and Jewellery Shop’. The stall prominently displays the sign ‘Fixed Price’ which I interpret as “we do not bargain, take it or leave it”. Belatedly I consider that the sign gives assurance that the owner won’t increase the price over and above what he had marked it as. However, I am taken by the shop’s flagship sign, more so than the goods on offer, for ‘Pappu’ is a nickname in northern India that roughly translates as a ‘common man’ full of innocence and simplicity. The name is used frequently in popular Indian culture, but I’m not getting the relevance of its application to the shop. I couldn’t bring myself to ask the sales staff in case I caused unintended offence. The best I could offer myself, as to a loose translation, was that it was an outlet owned by someone of local renown whose nature resembled that of the fictional buffoonish television character ‘Mr Bean’; portrayed convincingly by the British actor Rowan Atkinson. My interpretation was admittedly probably way off the mark. The owner could have just as easily been a cranky old man that was fed up with wealthy Westerners wanting to haggle him down by a few rupees, or those who spent hours sifting through his goods and then walked away without transacting a sale.

I find a reclusively positioned jewellery shop in a lane just off the chowk. It is entered by a low and narrow door that gave no hint of the treasures that lay within. The shop sells traditional Indian artefacts and tribal jewellery but the owner informs me such things, beautiful and precious as they are, are not so fashionable now. Indians see them, he says, as remembrances of the dead, out of date, or just plain old fashioned, and prefer, as they always have, jewellery of high quality soft gold of the 24 carat kind. My eyes gaze intently at each piece, my mouth gaping wider than my wallet has ever been capable of. Fortunately my tongue had sense enough to hold its place. I count my remaining money and contemplate a slim diet of lassi’s and street-bought bananas for the remaining three days. Airline food will rescue me from starvation on the fourth. The owner and I talk at some length, his assistants every now and then repositioning pieces already placed before me or emptying some extra morsel of rare crafting from inside one of several Hessian bags bought out for my deliberation. A solid silver tribal ankle bangle, a wedding necklace of delicate chain, a set of enamelled earrings. I was like a kid caught in a lolly shop, yet I will have to sleep on his offer. I might not be able to afford the bananas, and might have to supplement my rations with complimentary biscuits at the hotel. I have some counting to do.

Weighed down by such thoughts I journey on through numerous alleys and laneways, arriving at length before the ‘Little Tibbet Restaurant’, the two ‘b’s’ in the restaurant’s sign suggesting this was no ordinary kitchen of exotic food, that it had substance more than most. They sold vegetable dumplings, ‘momos’, the sign said, and ‘special momos’ at that. They were cheap, but good. I ordered and ate far fewer than I should have, and failed to order what I could have easily consumed. Momos devoured, the thought of possible jewellery purchases still heavy at my heart, I press on. A woman I had encountered earlier offers me her ‘final knock down, can’t go any lower’, price on a shirt I had previously expressed no interest in. I held to my resolve, but thanked her for her continued enthusiasm. I pass an ashen grey cat whose glass green eyes are fixed upon some item of prey that eluded my sight. Then in turn I encounter two sparrows sitting in shelter below an upturned human powered metal ‘trundle’, one of a wheeled pair positioned side by side in anticipation of collecting street refuse later that day, a solitary pigeon resting atop a stone cornice carved in the form of an elephant, a cow quietly drinking from a water trough, the verandah above newly washed sparkling clean, and a sign denoting the location of the ‘Hotel Suraj’ hanging prominently from an awning. House crows abound but I spy no squirrels anywhere. But everywhere that appropriate space allows are spread intricately stitched sheets of antique patchwork cloth, each weathered piece of fabric silently calling, tempting like sirens, in hope of a sale.

Tourists gather at the fortress battlements. I join the throng, and jostle for a vantage point that allows opportunity for photography without the prospect of a fall to my death. Beyond the flat-roofed houses of Jaisalmer is the distant Thar Desert, and Pakistan. There are no high-rise towers to clutter or obscure the vista, but yesterday’s royal cenotaphs are prominent, the farm of wind turbines more so. Like sentinels they dominate the horizon, up close they do not interrupt and thus you ‘see through’ them. The narrow alleyways lead me back past the Ratneswar Mahadev temple, its once decorative stone figures etched and worn, and the Laxmi Narayan temple, this dedicated to Vishnu, or ‘Narayan’, with his consort Lakshmi, the goddess of Love, Beauty and Prosperity. Not too distant is a shop that sells t-shirts. Each is hand painted by the ‘artist-proprietor in residence’ with an image of a rock star; Mick Jagger, Jimi Hendrix and Bob Dylan seemingly providing ‘stock in trade’ faces. Tempted as I am …. .

In the main chowk an aged musician, resplendent in red turban, has taken up residence by a wall. There he plays away at an instrument a little like a primitive cello, its strings of string few in number, the bow a cleverly warped branch of narrow width and moderate length. This device he deftly works to the joyful accompaniment of his voice, the gravelling melody of it like happy birdsong. I’m chuffed. A small piece of cloth sits at his feet, and there upon collect an ever growing number of paper bank notes. He graciously thanks the giver of each one. There’s a record album here in the waiting. He could come to Adelaide’s world music concert, and there’s a tribal group at the Sunderbans Tiger Camp that could team up as a great double attraction. But by the ever present joy in his voice, I suspect he was happy just where he was.

Later that afternoon I find myself comfortably ensconced in a washroom conveniently positioned alongside an open-air cafe above the fort’s First Gate. Outside it is warm and sunny. It was, simple as it was, to have been a great moment of satisfaction in an altogether great day. Except that it was spoilt by the thunderous passing overhead of a jet fighter. Talk about timing. I couldn’t get out of that washroom closet fast enough. I fumbled the door latch, I fumbled my belt buckle, I knocked my knee on an ill-placed terracotta pot of generous and unshifting dimensions. Too late. It might have been a ‘Sukhoi’, it might have just been a humble ‘MiG’, short for Mikoyan-Gurevich Design Bureau. I wasn’t about to get fussy. Either way I missed whichever of the two aircraft it definitely was. And whatever the make of that jet fighter it did one solitary low fly over, and I missed it. I didn’t even get to enjoy the after-scent of burnt aviation fuel. I looked out longingly for a return performance, but it just didn’t happen. Not a speck in the sky. And the pilot had no idea that I, sad, spurned and miserable figure that I had suddenly become, was waiting on the battlement for his return.

***

The battlements of the Jaisalmer fortress look out in Time. They are not constrained by space or place. To the west, and just out of view, rest the ruins of Mohenjo-daro, and the lesser Chanhu-daro and Lohumjo-daro. To the north, and at a greater distance, is iconic Harappa. They are the dead cities of the extinct civilisation of the Indus Valley, a culture now known to have been far more extensive in its sway and influence than that upon which archaeologists first centred their efforts. A culture that can be seen as providing the formative mould on which Classical and Modern Indian civilization partly rests; like the Etruscans were to Rome, and the Mycenaeans of Homer were to the Classical Greeks of Thucydides and Aristotle. By the 3rd Millennium BCE cities such as Harappa and Mohenjo-daro, these being contemporary with the civilizations of Mesopotamia and Egypt, likely boasted populations of 35,000 or more; no small an administrative and agriculturally centralised achievement for the time. Certainly the surrounding landscape was capable of agricultural production substantial enough to support such population centres, and it was the outcome of the agricultural potential of the Indus plains that allowed the development, and later dramatic expansion, of what is commonly called the ‘Harappan Culture’, and its regional variants. Like the civilizations of the Nile, Tigris and Euphrates, that of the Indus Valley was heavily reliant on nutrient rich sediments deposited annually by floods. The discovery and utilization of burnt-brick for construction and flood control provided an important advance in the foundation and expansion of Harappan culture, for sun-dried bricks are easily destroyed by rain and floodwater, and stone was not readily available for the majority of the Harappan sites. The production of burnt bricks is dependent on a reliable source of timber, which was abundant in riverine tracts of forest, and in some areas of the Indus catchment still is.

The political and economic status of this culture is uncertain for it is difficult to ascertain the nature of individual cities, and even with Harappa and Mohenjo-daro, the two sites that stand out, it is unknown if they represented anything resembling the capital or capitals, of single or independent political units. Mohenjo-daro was excavated between 1922 and 1931 by the Archaeological Survey of India under Sir John Marshall, this being continued by others after the partition of Pakistan and India in 1947. The extensive mound system at Harappa was first reported by Charles Masson in 1826, with methodical excavations first being carried out between 1920 and 1934 under the direction of Pandit M.S. Vats, also of the Archaeological Survey of India. Later excavations there revealed evidence of a pre-Harappan society.

Many features of Harappan culture indicate aspects of the religion of the Vedic period and of later developed Hinduism. Symbols such as the swastika were already of religious importance. A religion dominated by one god is suggested, and this divinity has traits similar to that of Shiva. There also existed a mother deity that shares traits with that of Parvati, the consort of Shiva. Trees and tree spirits, and particular animals, were also of religious significance. However, sometime in the early 2nd Millennium BCE the culture broke up. Causes have been attributed to those of climate change, redirection of dependent river courses, and the entry of Aryan peoples, if not actually RgVedic Aryans.

It was a long time ago, and by 6 pm I am back within the confines of the hotel. It is my third last night in India.